In the recent BSTS summer 2025 newsletter there is an excellent article by our very own numismatic expert Justin Robinson, Byzantine Gold – the two faces of Jesus. In it he looks at two gold solidus coins minted during the reign of Justinian II. The first coin minted between 692 – 695AD portrays a Shroud like image of Jesus. The second coin minted circa 705AD during his second term as Emperor portrays Jesus as clean shaven with curly hair. Justin goes on to explain how this strange anomaly probably came about and how different engravers may have at first had access and later no access to the Image of Edessa, probably the Shroud of Turin as we know it today.

In his introduction, Justin says “For centuries after his public execution, there was no consensus among artists on how to depict the face of Jesus of Nazareth. The Bible makes no mention of his physical appearance, preferring instead to focus on his words and actions. Contemporary Roman, Greek and Jewish accounts of his life provide us with no evidence either. The earliest known depictions of Christ reflect this uncertainty. In some illustrations he has long hair and a beard. In others he is clean shaven with curly (or short) hair”.

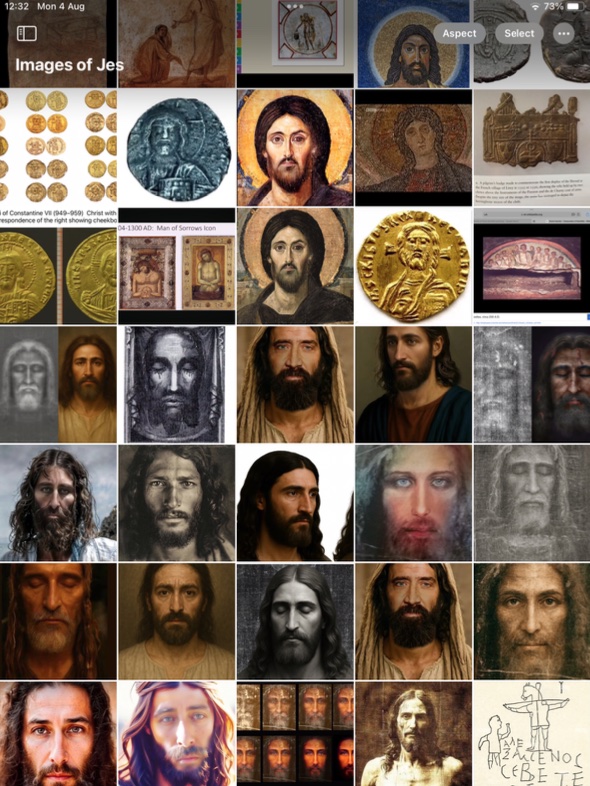

Of course, this begs the question: what did Jesus look like? Today, all of our modern depictions portray him with long hair and a beard. In fact, very much like the image on the Shroud. Of course, those who believe it to be Medieval would say ‘Well, the artist just copied artistic icons and depictions that had been previously painted’. Is this the case though? Does history reveal anything?

Early Depictions of Jesus

Probably the earliest depiction of Jesus was an insulting graffiti carved onto a wall on the Palatine hill in Rome. It dates somewhere between the first and second centuries AD. It is a crude drawing of a man being crucified with the head of an Ass and a young man beside him with his hand raised in prayer. The inscription reads “Alexaminos worships his god”. Which obviously applies to Jesus. It also gives a brief insight into how Christians were perceived at that time. There was a need for secrecy and discretion, especially concerning the burial Shroud of Jesus.

Tacitus calls Christianity “the deadly superstition,” one among “the shocking and shameful things” which flow into the city of Rome. He explains that the Christians were “hated for their crimes” and reports that they were brought to trial for hatred of the human race. The Shroud which would have been in their possession would need to have been kept hidden. The image not being made by human hands nevertheless could be confused with the fourth commandment “You shall not make yourself an image”.

Portrayals in the form of paintings of Jesus did not start to appear until the third century. It is worth bearing in mind that they would have been painted by gentile converts who would now be in the majority. The paintings depict Jesus in various ways; i.e. as the Good Shepherd (see below left), or raising Lazarus from the dead, or various miracles. An early painting now held at Yale University is the Dura-Europos circa 232AD which depicts Jesus healing the paralytic (see below right).

All of these early paintings show Jesus as a young man with short hair, clean shaven and wearing a Roman toga. Much as today’s society, beards came and went as a fashionable thing to have, so the clean shaven Jesus may also help date the paintings to a time when to be clean shaven was the fashion.

The oldest catacombs in Rome are the Flavia Domitilla, who was the ill fated daughter of the cruel Domitian (81-96AD), her husband was put to death and she was exiled because of their Christian faith. A painting in the catacombs portrays Jesus as a Roman emperor and his Apostles all dressed in senatorial garb with short hair and clean shaven

As we get into the fourth and fifth centuries, some depictions of the ‘Syrian’ Jesus start to appear alongside depictions showing Jesus with long hair but still clean shaven. The Roman garb no longer being used. A sculpture of the head of Jesus from the ancient city of Antioch from the Theodosian period (370-410AD) was found which portrays Jesus with full beard and long hair. Athanasius who was Bishop of Alexandria 328-373AD had described how “an image of our Lord and Saviour at full length “ (was taken from Jerusalem to Syria in 68AD), “two years before the destruction of Jerusalem, all the Christians left and betook themselves to the kingdom of Agrippa, at which time many other things belonging to the church, this image was also carried away and ever since remained in Syria” (in which was the important city of Antioch).

Little is known about the early days of the Shroud although it is mentioned in various texts, including the lost gospel to the Hebrews and the mysterious hymn of the Pearl. Up until Constantine’s edict of Milan, persecution was an ever present danger. Did the Shroud go to Antioch to be hidden later in Edessa, or was it as the legend of king Abgar says: the Shroud being gifted to Abgar by one of the first disciples at which time his leprosy was healed? The legend goes that his son reverted to paganism which led to the Shroud being hidden and forgotten about.

The historical records re-emerge however in 525AD. A chance discovery by workers repairing a wall in the Mesopotamian city of Edessa would change the way Jesus would be depicted forever. High up on the wall, they stumbled upon a hidden niche and within that small space they found a container with a strip of linen carefully folded inside. It is not really known how or why the cloth got there? Maybe the legend of Abgar grew up to explain it?

This cloth, which became known as the Image of Edessa or Mandylion, was the catalyst for many paintings of Jesus. “Depictions of the bearded face on the Edessa cloth, soon began to appear throughout the Christian world. They became known as the ‘Pantocrator’ (all powerful) image. Within a few years of the discovery, the Basilica in Ravenna, Italy had a beautiful mosaic of Christ based on the distinctive face. At around the same time, St.Catherine’s monastery at Mount Sinai, nearly three thousand miles away, received a new wall painting with features that also closely matched the face on the mysterious cloth.

Byzantine Coin Images of Jesus

Over the next few centuries the Byzantine emperors minted many gold solidus coins that closely matched the face on the cloth, even showing injuries to the left eye and cheek.

The next major event in the life of the image bearing cloth was August 15th 944AD. A date still venerated by the Eastern Orthodox Church. The emperor Constantine VII agreed with the then Muslim leaders of Edessa to release to him the Image (Mandylion) in exchange for the return of 200 high ranking Muslim prisoners and a huge amount of money. On August 16th the casket containing the cloth was paraded round the city walls for the people to see. There was a massive celebration. The casket was then taken to the Hagia Sophia. On January 27 the 945AD the emperor Constantine Porphryognitus took power and issued gold coins bearing an impressive Shroud-like image.

Some sceptics obviously doubt all of these links and depictions of the Shroud because if true, it would rule out the medieval Shroud proposal. However this link has been strengthened by Justin Robinson’s recent discovery of two more common ‘mass produced circulating coins’. These bronze follis coins minted during the reigns of John I Tzimiskes (969-976AD) and Michael IV (1028-1041AD) show incredible similarities to the image on the Shroud. His BSTS Newsletter article A Compelling Case for Authenticity includes illustrations of the John I Tzimiskes coin, which represents one of the earliest coins of this kind. As Justin says in his interview with Guy Powell, he believes these coins prove conclusively that the engravers who produced the dies for the coins must have looked at the face on the cloth.

The Shroud, or Image of Edessa as it was then known, was then kept in the Pharos chapel along with all the other sacred relics until at least 1204AD, which is it went missing for the next 145 years. In 1204 the French and Venetian crusaders captured the city and sacked it. Amongst the stolen artefacts were four Bronze horses from the hippodrome which were taken to Venice, where they can still be seen in St Mark’s Square. Most of the relics were taken to France.

Was this when the Shroud was taken France, or was it later when Baldwin ‘the broke’ sold it to the king of France who subsequently gifted it to Geoffroi de Charny because of the sin of Simony? Or did the crusader Othon de la Roche, who became governor of Athens, take it (and was therefore rebuked in a letter to Pope Leo) before taking it to France where it reached the custody of Geoffroi de Charny through marriage? Or did the Knights Templar take it as some suspect, whose secret group was accused of worshipping a bearded head and whose leaders were subsequently burned at the stake?

Whilst we do not fully know how the cloth came to be first displayed in Lirey, France, there is enough evidence now to show that the Shroud was not produced by a medieval artist and that it does in fact bear a remarkable likeness to many early portraits of Jesus, which include several features such as the line across the neck and forked, uneven beard which indicate that these portraits had been copied from the Shroud image.

It is therefore our hypothesis that whilst not realising it, the depictions of Jesus that we all know and accept, whether in churches, films, books etc, all originally stem from the Image of Edessa, which we believe to be the Shroud of Turin.